What is experiential cinema

This article is also available in:

![]() Italiano (Italian)

Italiano (Italian)

As promised in the last article, we’ll continue to analyze the cinema of the future in its immersive form. Immersivity certainly linked to the experience it can create in the viewer. In this article we will therefore go on to talk about experiential cinema through old and new storytelling, first person, greater involvement of the viewer and the five senses, and more data and artificial intelligence.

Indice

What is a media, or “mediated story”

The characteristics of traditional cinema

Each media has advantages and disadvantages. Or, we could say, possibility and impossibility. Going into details, let’s quickly see the five peculiar characteristics of the media at the center of our attention: cinema.

- Static and linear narrative structure

- Single or dual mode

- Episodic

- Third person perspective

- Passive audience

Static and linear narrative structure

It’s at the basis of cinema: a one-way narrative structure with beginning, development, climax and end. Fixed and static, it obviously cannot be changed by the viewer. Sure, there are Flashbacks or Flashforwards, but they don’t fundamentally change this approach to storytelling.

There is usually a causal chain: each passage narrated in the script leads to a subsequent passage which is a consequence of the previous one.

And the movies, of course, don’t change over time. Except for very rare cases of errors or problems occurred after the release of the film (for example Kubrick cut the last minutes of The Shining after its release in theaters), these remain the same from the moment of publication, and forever.

A good analysis was made in 1992 by Prof. David Pinault in Story-Telling Techniques in the Arabian Nights.

Non-linear structure in traditional cinema

In postmodern cinema there is actually a concrete attempt to modify this linear structure. Often attempts are made to “weave” the story, leaving the viewer to use intuition and irrational instinct to understand the film, while logic and drama are dissolved and diluted.

The linear structure often develops into a symphony composed of several parts with a non-linear structure. We will understand better in the following sections how this will develop even more in experiential / interactive cinema, forming various personalized narratives (which is reminiscent of videogames).

Single or dual mode

By this we mean that cinema involves a maximum of one or two senses, sight and hearing. Clearly the current cinema is always dual, as in the “single mode” category we can only insert silent films.

Over the years, various attempts have been made to improve the involvement of the other senses. We think of great directors who manage to convey the sense of taste to the viewer, for example in films such as Eat Drink Man Woman, Ratatouille or Mid-August Lunch. Clearly, it is a trick to our brains. But ultimately, cinema itself is.

Episodic

According to Prof. Jason Mittell in his book Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary Television Storytelling, current cinema and media are generally episodic; that is, they tend to develop around an event or a series of interrelated events. This is even more true, of course, in the world of journalistic media.

A story is told based on facts and events, real or fictional. It is told from the point of view of the narrator, which makes it easier for the viewer to enjoy but at the same time empathically distances him from the story.

Third person perspective

This perspective is an important feature in our analysis. In fact, although possible, in traditional cinema first and second person perspectives have always been little used. In the history of communication in general, it was abundantly used only in the radio of the first half of the 20th century.

Heart of Darkness, first-person radio adaptation

As an example, consider Joseph Conrad‘s Heart of Darkness. It was adapted for radio in 1938 by director Orson Welles (famous for having made Americans believe they were under Martian attack through the radio show War of the Worlds, in the same ’38). The goal was to have the protagonist tell the story in first person directly. Interesting how Welles himself, at the time new to cinema, tried to persuade RKO Pictures to make the film version.

It had what it takes to become one of the greatest films of all time and, perhaps, raise public awareness on issues that instead, misinterpreted, led to the Second World War the following year. But it was the use of the first person, in addition to the political themes little loved by the majors, that probably pushed Hollywood to not consider its feasibility. It was a drastic break from the rules, and the world wasn’t ready for it yet.

In fact, Coppola tried to recover in 1979 with Apocalypse Now, only freely inspired by the novel “Heart of Darkness” as it is set in Vietnam and not in Africa. It is certainly too late to assist peace in Europe and in the world.

First person in the history of cinema

There are some sporadic cases of filmic use of first-person narration, especially in its early years. Sometimes little known cases, but which somehow tried to change the way of seeing things. First of all I think of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde of 1931, better known in Italy as Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, by Rouben Mamoulian.

Other cases were William Dieterle‘s 1934 film The Firebird. Or even Lady in the Lake shot in 1947 by Robert Montgomery, and Dark Passage by David Goodis of the same year.

Two other examples, decidedly more modern, we will see shortly in the section on experiential cinema, as they are more useful for a comparison with the cinema to come.

I have cited only examples of works in first person, because talking about works in the third would be impossible or useless… They are practically almost all the films in existence. And then because, with a view to creating the cinema of the more experiential future, I believe that these ideas must be well taken into consideration.

Then you will tell me what you think, I’m interested in being closer to the technical world than to film criticism.

Passive audience

As we said, the story in the current or past media is told in the name and on behalf of the narrator. Whether it’s the writer or the director, the journalist or the speaker, everyone shows you what they want. Have you ever wanted to look at something to the side, or behind the camera, but the direction didn’t show it to you?

It happens particularly often with sport on TV, and it is perhaps for this reason that television itself is among the first media to have “progressed” towards a direction decided by the viewer. In Italy, as Wenner Gatta mentions, when the “Spidercam” was inserted on the football fields, the viewer could choose with the remote control whether to see the meeting with the classic direction or through the spider camera only. And from there, above all Sky has continued to develop technology a lot by exploiting multiple transmission channels for the same event.

After a study of the cinema that was, and still is, we are finally going to analyze the characteristics of the new cinema, projected towards the future, to also understand how to overcome the problems of the last 127 years.

The characteristics of experiential cinema: the future

The five characteristics that we will be able to find, all or in part, in the cinema of the future, according to what technology currently makes available, can be:

- Immersivity

- Interactivity, non-linearity and sociability

- Multi-sensory presentation

- Algorithmic, customized in real time thanks to data

- First person perspective

Immersive Cinema

We already know some partially experiential media. We think of immersive virtual reality and augmented reality platforms. As we saw in the last article, these are fully inserted in the line of continuity between real and virtual world hypothesized by Paul Milgram.

Immersion means “enveloping the user in a real physical space using augmented or mixed reality on a portable or wearable device, also including haptic interfaces“.

I found one of the first practical examples in the paper “Situated Documentaries: Embedding Multimedia Presentations in the Real World“, by Tobias Höllerer, Steven Feiner and John Pavlik and taken from the International Symposium on Wearable Computers of 1999.

Image from “Situated Documentaries: Embedding Multimedia Presentations in the Real World“.

These “set documentaries” were entirely based on wearables, to integrate novels and documentaries in real-world locations. The system is very reminiscent of the current AR glasses, obviously with the technology available in 1999. It was a backpack with GPS tracker and 360 ° video camera (developed by Shree Nayar, of Columbia University), a type of handheld computer with graphics, audio and video, and augmented reality glasses capable of signaling in the real environment the points of interest. It was called MJW (Mobile Journalist Workstation).

The glasses could also reproduce rudimentary 360 ° videos superimposed on the real, and the gaze was the main aiming system. By staring at an object in the real world for at least half a second, it was selected producing related info and multimedia files. You could also travel in time by touching the desired year on the handheld display.

A great example of what augmented reality will be 20 years later. AR is in fact developing rapidly, becoming in common use since 2018 following the implementation in iPhones of the native ARKit api (which, by the way, I believe to date is the latest noteworthy innovation in the smartphone field).

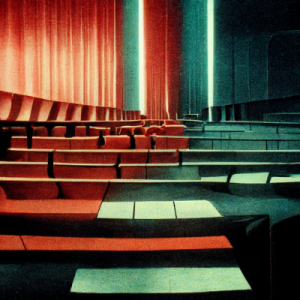

The first point of our cinema will therefore be immersion. But certainly a different immersion from that seen so far. The basis will in fact be the story told, the cinema. We will not immerse ourselves in the world, we will not immerse ourselves alone or in virtual common environments. The immersion will be produced by the 360 ° screen, by the stereoscopy, and by the “hall”, or dome, with inside elements directly linked to the narrated story.

The writers will have to be really good, to develop plots that make the viewer feel “involved”, without being taken for granted. As is obvious, the first thing that jumps to my mind: to keep the protagonist of the story constantly seated, who must impersonate us spectators. It is at best a starting point that should not be underestimated, but above all the brain storming will be really interesting in the early days.

Interactive, non-linear and social

Word to the viewer; choice. These may be the keywords for the non-linear structure of experiential cinema; which is therefore more complex.

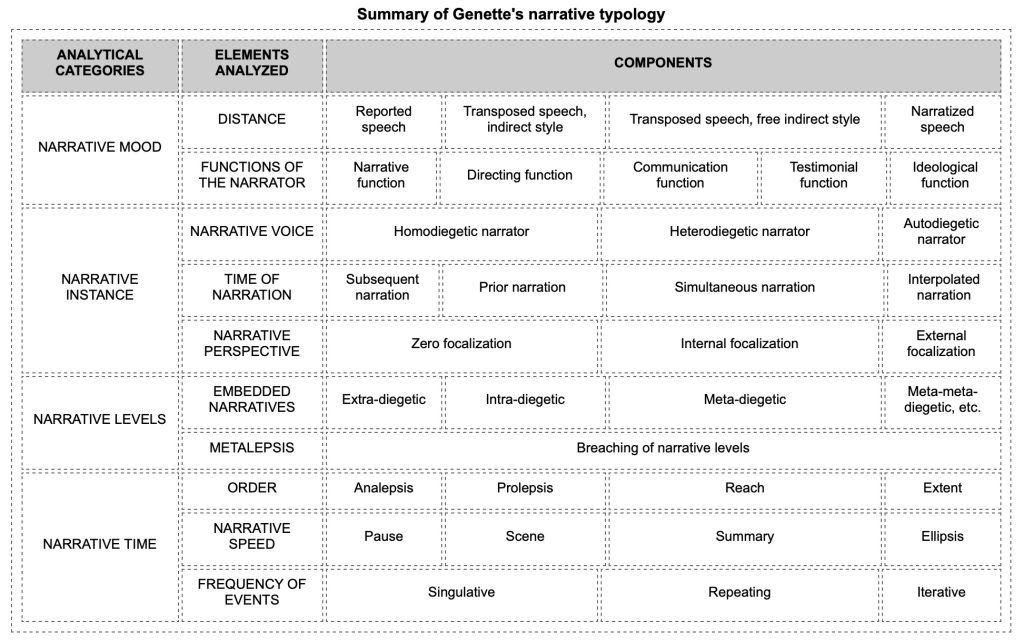

Although without particular rules, it maintains its own logic based on temporal sequence (or order), duration and frequency, which are the concept of division proposed by the French essayist Gérard Gennette in the field of literary fiction, then introduced in the field of film criticism by Andre Gaudreault and David Bordwell.

The order of events in the stories

In this section we open a general parenthesis on the stories; there are in fact characteristics in common with the future immersive cinema. Gennette clarified that the event could have occurred:

- before the narration (analyses or flashbacks)

- in the future (therefore only announced or expected, the prolixes).

- Again, events can be narrated in a different order from how they happened (anachronia), used to make the story more compelling.

- More rarely there can be a movement between one narrative level and another (metalepsis).

An example is the “author’s metalexy”, a sort of passage by the author from external to internal to the story, or conversely if a character becomes a narrator.

Another literary example is of the poet Virgil, who “kills” Dido in canto IV of the Aeneid, or Diderot who writes in Jacques the Fatalist: “Who could prevent me from marrying the Master and making him a beak?”. Both examples taken from Armando Mollica Bonivento‘s doctoral thesis at the Ca’Foscari University (in Italian), which I invite you to read for greater understanding.

The duration of events in the stories

So, after the order (event that happened before, future event, narration in order different from the real or passage between different narration levels), we have the duration. Also definable as the “rhythm”, the “speed” at which events are told.

We can mainly divide it into four types:

- ellipses (very accelerated rhythm), with frequent chronological jumps;

- synthesis (relatively fast pace), in which a story is summarized in its main points. They can be of variable length.

- scene: relatively slow, it is the classic narration almost in real time. An example are the dialogues;

- descriptive: no progress in history, we stop to describe a certain moment.

Clearly, these types can be combined. We can have, for example, a synthesis inserted within a dialogue.

The frequency of events in the stories

Frequency is nothing more than the relationship between how many times a certain event occurs in reality (even invented), and how many it is told. If, in practice, the same event is narrated several times (or the same statement of a character repeated).

I leave you the link to an interesting article on the issue, from which the following image is taken.

The cinema of the future has an intersubjective non-linear structure

After this long interlude, let’s try to understand why the story, or the screenplay, is decidedly more complex for the cinema of the future. In fact, all these elements must be inserted within an intersubjective non-linear structure. That is, the story can go back and forth in time, in an environment common to other viewers who may want to make different choices from ours.

Intersubjectivity is the biggest problem to be solved in writing new scripts. In fact, if interactivity is a concept already well known thanks to video games, interactivity in common between several people, with necessarily a screen that shows everyone the same images, presumes that a small democracy is created inside the room.

The intersubjective non-linear structure has a great advantage: it respects the viewer. It grants the right to choose one’s own story, to judge the morality of some scenes. The viewer becomes the center of the film as well as a part of it. The current cinema is definitely too one-sided, and if it has lived unchanged for so many years it is only for the simplicity (inherent in the characteristics) of using it as a means of political and commercial propaganda.

Thinking about the average use of cinema, which is also and above all a moment of relaxation and not very active entertainment, we must not however fall into the temptation to insert excessive “gamification”, transforming it into a video game. I mean, nowadays we go to the cinema to relax with friends or family, to spend time without thinking too much. And choosing implies thinking … This is why interactivity must be limited and not even mandatory, and it probably won’t be the top priority in creating the cinema of the future.

We will see in some future articles why interactive cinema has not been successful in, albeit few, past experiences. But it is related to this.

Multi-sensory presentation

Experiential media may seem like something new in recent years, but it’s not entirely true. For centuries, humanity has developed its peculiar characteristics, improving the technology available in small but constant steps.

Wearable devices to engage the senses

According to what was reported by the Prof. John V. Pavlik in the book “Journalism in the Age of Virtual Reality“, the first experience of” wearables “devices can be summarized in the Chinese invention of the ring / abacus, wearable measuring instrument dating back to the Qing dynasty of the seventeenth century.

Following in Europe, in 1780 the “pedometer” was developed, a step counter, to arrive in 1965 with the American attempt (unsuccessful) to create the first exoskeleton (Hardiman) to allow humans to lift up to 650 kg.

In recent years, developments have certainly been much faster, also thanks to the logarithmic scale of the technology that hardly stops once it has started. To understand, did you know that in 2004, just 18 years ago, the GoPro wearable camera came out … And that it even used 35mm film?

Cinema stimulates us physiologically and sensually

My body is not just an object among all objects, but an object sensitive to all others, which reverberates at all sounds, vibrates in all colors and gives words their primal meaning through the way it receives them.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty in Phenomenology of Perception

At the beginning of this paragraph I inserted the trailer for the film Piano Lessons, Jane Campion‘s 1993 masterpiece. I chose it as an excellent example of how current cinema tries, in more or less orthodox ways, to deceive the brain in order to involve senses not directly involved (touch in this case). I also invite you to review the last article which talked about Matthew Shifrin and his Legos for the blind.

This is the magic of cinema. Art in this sector has reached unimaginable heights, even if you try to think about how to go further. How to materially stimulate the other senses. Although already in the 1940s, the philosopher Siegfried Kracauer wrote:

The material elements that appear in the films directly stimulate the material layers of the human being: his nerves, his senses, his entire physiological substance.

Siegfried Kracauer

How to involve the five senses in the cinema

How then to involve the five senses, or at least more than two, in cinema? It will be necessary to proceed in stages, as technology allows it. So let’s consider the experiments done in the past, to later understand how WE can engage the five senses for our viewers.

Touch

Meanwhile, the touch: William Castle, in 1959 shot the horror The Tingler. He inserted a vibrating device called “Percepto!” Into the seats of some cinemas, which was synchronized with the action. Castle himself was an evil genius … Before the screening of Macabre in 1958, he had everyone deliver a $ 1,000 insurance policy in the event of death or fear during the film. Then during the 1959 film House on Haunted Hill, he let a phosphorescent skeleton enter above the stalls. Based on a pulley system called “Emergo“.

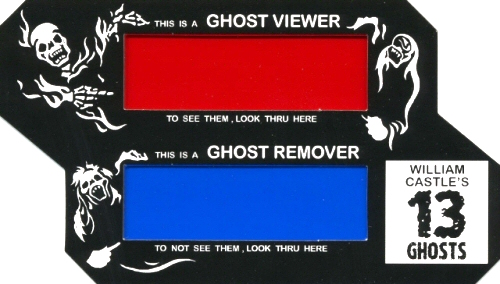

And finally there is “Illusion-O“, launched with the film 13 Ghosts: all the elements in the frame, with the exception of the ghosts, were subjected to a blue filter. The ghosts instead had a red filter, and were superimposed on the frame. The audience received cards with red and blue filters: looking through the blue filter, you couldn’t see the ghosts. Through the red filter, however, they could be seen.

Still on the touch, obviously the modern 4D cinemas that we all know have the entire vibrating chairs, as well as ropes that touch the legs, fans for the wind effect (hot or cold) and sprinkles of water for humidity.

Smell

Smell: a strategy was adopted by John Waters for the 1981 film Polyester. This is the “Olorama” system, basically cards with scratch numbers. Each number has a smell (rose, pizza etc …), which can be smelled at the required moment (a small number appeared on the screen).

Another 1960 attempt was Smell-O-Vision, used only in Scent of Mystery produced by Mike Todd Jr (son of the famous Mike Todd Senior, author of Around the World in 80 Days). Smell-O-Vision involved the introduction of up to 30 evocative smells into the stalls through tubes that led to individual seats in the room, with perfume bottles held on a rotating drum.

Today a company has taken up the concept in a modern industrial production, called Olorama. With whom it would be nice to collaborate; objectively, the system seems much more functional than smelling cards (then actually reused only in a couple of children’s films).

The criticisms he received are interesting. According to the Times, some viewers complained of delays between the smell and the scene, others found the scents mixed in an unpleasant way, Henny Youngman said he didn’t understand the film because he had a cold.

Other inconveniences to pay close attention to are nausea and headaches caused by too strong and persistent fragrances, possible discomfort, distractions and heavy air.

For the sake of completeness of information, I quote Walter Reade Jr‘s AromaRama. Key difference with Smell-O-Vision? Simply, the AromaRama used the air conditioning system for the diffusion of aromas. Cunning.

Eating with another is a way of saying: “I’m with you, I like you, let’s form a community together”.

Thomas C. Foster

Taste

We have seen touch and smell, taste is obviously lacking. Although progress has been made towards systems of “transmission” of taste (through objects to be licked), I do not think they are yet developed enough and, above all, we are not yet ready to welcome them. And I don’t know if we ever will …

However, during some screenings of Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory, Wonka chocolates were provided to the spectators. And from this I had the idea of directly providing the screened food, really to the spectators. A double advantage: for the identification in the film, and for the cinema economy and customers who would respectively sell and buy better food than popcorn and Coca-Cola.

I soon discovered how this idea is not exactly original: in 2012 in London, more precisely in Notting Hill, Edible Cinema took place. It was a collaboration between the Soho House team, organizer Polly Betton and experimental food designer Andrew Stellitano. Basically, each present had numbered bags and glasses containing food and drink, on the armchairs there was also a menu explaining the meals, and a woman appeared on the side of the screen during the film to indicate the time to eat or drink each number.

Algorithmic, customized in real time thanks to data

In a data-centric society, cinema cannot stand by and watch. Of course, in respect of privacy and possibly without using this data for not very noble purposes.

A great use could come from the geolocation inside the dome, to eventually send different signals to the different spectators. But, above all, it will be possible to take into account the direction of the gaze of the latter to understand what is more interesting, and to have a more passive “input device”, and therefore less tiring, due to the interactivity we have just talked about.

Other anonymized data, such as physiological responses moment by moment, may be useful for the development of subsequent films and evaluate the reactions of the audience. Which, in a subsequent development of experiential cinema, can also be exploited within the same story (for example, interactively manage volumes to increase or decrease human reactions).

Women’s Aid, a prime example of algorithmic interactive advertising

At World Women’s Day in 2015, an interactive blow-up depicting the face of a woman victim of violence was installed in the Canary Wharf business center in London. A face detection camera was used to update a counter and change the image whenever a passerby paid attention to the advertisement. It was a typical example, albeit in the advanced advertising sector, of using data to modify the result obtained.

Artificial intelligence for storytelling

Already today many stories are created with artificial intelligence, as for example the American Associated Press does. The Times also created an algorithmic robot, the QuakeBot, which automatically acquires data from the U.S. Geological Survey, the US organization of earthquake analysis, to automatically write the complete article with magnitude, epicenter and time. The human editor only has to verify its correctness and publish.

These robots, these artificial intelligences, are led to the development of increasingly engaging, interactive and multisensory stories. What will be fundamental for the cinema of the future, to assist human screenwriters in the writing of increasingly complex and autonomously unmanageable stories.

Furthermore, they will be able to exploit the data present in the world, and in the cinemas themselves. To create “tailor-made” stories for the target audience.

Artificial intelligence itself is, and will increasingly be, used in technical video production. Google, for example, has the Jump compiler (well described in their own paper), which deals with the union, stitching, of 16 high quality video streams to obtain a complete 360 ° VR video. The main result obtained was the elimination of much of the latency, to therefore increase the sense of reality of the image shown.

Ultimately, AI will certainly be the center of attention. And, to avoid controversy, it must also be used with lead gloves, focusing on privacy and the importance of the human being.

First person perspective

We already know some partially experiential media. We think of immersive virtual reality and augmented reality platforms. As we saw in the last article, these are fully inserted in the line of continuity between real and virtual world hypothesized by Paul Milgram.

These are clearly in the first person, as the real protagonist of the story is ourselves. Experience is given by contact (although still virtual), and by direct observation of objects and events in the ways we like best.

Experiential cinema will often have to be in the first person. This is unlike most of the present and past films, which instead aim to tell us stories with eyes outside the story. But ours will be a different first person: we will be the spectators, the main character. Recently, in 2016, the film Hardcore, directed by the Russian musician Ilya Najšuller, had a good success. Evidently producing cinema from a cultural background outside of it helps to take risks and innovate it.

The whole Hardcore is shot in first person. I believe the success is well deserved, and it is a good point of reference for the cinema to come. A way of narrating video games, which invites us into someone else’s life, looking at the world through his eyes. Well, I think the only difference is that it will have to be our life, inserted in the new cinema. I know, it’s scary, but the writers shouldn’t tell us that either …

I also want to mention another film, not entirely in first person (the protagonist can be seen in various scenes, removing the effect of total identification) but which has a decidedly more constructed and engaging plot than Hardcore: Enter the Void, from 2009, directed by Argentine director Gaspar Noé.

Two films that I recommend you see, first because it will be a special and different experience. Second, to get a taste (albeit reduced) of what cinema will be like in a few years.

To identify everyone in the history of experiential cinema

How can you build a film for many, which can realistically represent the life of each of them? Once again, the writers will have to do a great job of multiple introspection. By creating engaging but generalist stories, inserting characters who will also be new to the protagonist in the story. No known relatives, perhaps a distant cousin we didn’t know we had. Nothing more.

In 2015, on the occasion of the fourth international conference on Design, User Experience and Usability in Los Angeles, Aaron Marcus collected in a very useful book a series of information on the current relationship between computer science, the virtual world and human beings. Based on the assumption that each of us has our own culture and knowledge, the design (and therefore who creates it) must leave us the freedom to experiment, to have doubts and thoughts, it must build a world accepted by all the personal cultures of the spectators and, at the same time, propose his own idea of the universe.

We want and need to reflect, to understand. And this absurdly leads to the hyperrealism, that is, to a construction of the virtual world that is very faithful to the real world, in which to experience and be present in the first person.

The importance of sociality in the cinema of the future

We have seen, speaking of the first-person perspective, that technology now allows us to decide a place, at a given historical moment, and live virtually in it. But one thing will be important: we will have to live it with others.

Sociality is a theme that should not be underestimated: there is no life alone. To reconstruct the real in the virtual, other human beings (and living beings in general) must therefore necessarily be present. And a concrete interaction with them.

Basically, reality is an inherent concept in our mind. Many things are real to you and me, while others are only real to one of us. The “mediated” reality has an inherent complexity in this, mainly because it must be able to reproduce a synthesis of our personal realities.

Let me explain better with an example: Aurora has a habit of calling her mother in case of problems. In her reality, her mother is always present. He gives her advice, embraces her, offers her constant support. Marco, on the other hand, has a bad relationship with his mother. She has always had problems, she has tried for years to help her but to no avail.

Aurora’s reality requires a loving and very present mother, on the contrary that of Marco rejects her. The writers of the new cinema will therefore have to be able to fall into hyperrealism, without causing moral incidents with any of the spectators. How is this resolved? Important characters may, or perhaps should, be ambiguous. An ambiguous character that allows everyone to “accept” it by mixing their own inner reality with that reproduced and therefore “mediated”. In short, see them as you wish.

Ultimately, the “static” part of the real world, such as trees and houses, is always there. And easily reproducible. On the other hand, the human part, the social part, represents a definitely more complex choice, even if not insuperable.

The non-linear structure of these modern films provokes thought and encourages discussion. The way the story unfolds keeps us eagerly waiting for what will happen and leaves us to discover lots of things.